HOME • FUTURE OF SEATING • THE 90 DEGREE PARADIGM • SITTING AND ITS DISCONTENTS

CATEGORIES OF CHAIRS • SIT STAND TREADMILL • CONTACTS

COMMENT IN A BLOG

I. What is the 90 Degree Paradigm? • II. Initial Observations • III. Key Issues in Workstation Design • IV. Detailed Observations: Stress • V. The Insertion of Breaks • VI. The Nature of Breaks • VII. Breaks and Productivity • VIII. Summary and Conclusions

Bashir: 135 Degree Study

Workplace seating disease encompasses low back and neck pain, diseases of the extremities and carpal tunnel. We may also include circulatory and joint diseases, disorders and any other condition where extended sitting or standing is not listed as a primary cause but an exacerbatory one once the disease is established. Precise costs to society of workplace seating disease are impossible to establish, but they are certainly in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually, and rival the costs of cancer and diabetes.

If you accept that workplace seating disease is a fact, and the numbers cannot be interpreted in any other way, then you must also accept that there is a source, or a cause of that disease and that simple methods of inquiry may used to identify that source. In this case we are increasingly being told that “sitting” is the source, that sitting is “the new smoking” and that there is no recovery from the lifetime ills of extended sitting. But we are not being told exactly why that is so.

We propose a detailed inquiry into the source of workplace seating disease. Herein it is the method, rather than the fact, of sitting that is the target of our inquiry. Renegade Space advocates a variable posture model and does not see sitting as a monolithic activity with a single definition. The target of inquiry as follows will therefore be the 90 degree paradigm, the model for the nearly universal conventional workstation and its associated seating device.

I. What is the 90 degree paradigm? ∧

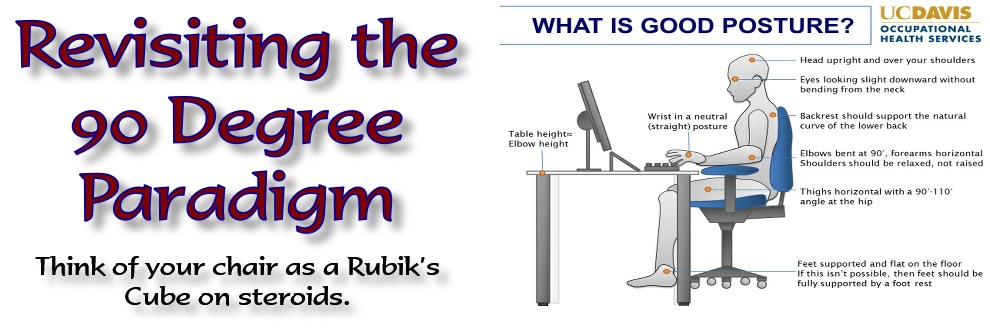

• For years office workers and the general public have been advised that the best, i.e. “healthiest” posture to maintain at a workstation is the one illustrated in the UC Davis Occupational Health Services graphic above and in countless sites across the internet: the body is upright, 90 degree angles at the elbows, hips, knees and ankles, feet flat on the floor. The issue of comfort is here somewhat inferred but decidedly less clear;

• For years office workers and the general public have been advised that the best, i.e. “healthiest” posture to maintain at a workstation is the one illustrated in the UC Davis Occupational Health Services graphic above and in countless sites across the internet: the body is upright, 90 degree angles at the elbows, hips, knees and ankles, feet flat on the floor. The issue of comfort is here somewhat inferred but decidedly less clear;

• The purpose of the 90 degree paradigm is to enable a worker to perform the monotonous task of operating a keyboard at a workstation. This requires a certain amount of precision, balance and extended stability. The posture therefore can be seen as an attempt to install discipline and structure into what would otherwise be an essentially mindless activity. It is a set of instructions dealing with how to use a conventional seating device to form a human interface with a computer. The 90 degree paradigm is the sole basis for the design of the modern workstation which encapsulates millions of workers;

• The origin of the set of the set of instructions is somewhat unclear; Cornell University has been active for years in the area. OSHA is another source. The instructions have been represented in hundreds of different venues with slight variations since the early 1990’s. Enforcement of any guidelines is also unclear, and probably untenable; according to their literature “OSHA will cite for ergonomic hazards under the General Duty Clause or issue ergonomic hazard letters where appropriate as part of its overall enforcement program.” For OSHA “ergonomics” covers a broad swath of industries and work situations; any concern they would have at the workstation would center on musculoskeletal disorder (MSD);

• While the paradigm may not always reflect real world use it remains as the master model or guide as to how a modern chair is to be used. Most critically, it is presented as a blanket design with no alternatives for variable seating needs. Even more sophisticated chair designs do not change the fact that the 90 degree paradigm remains at the core of our installed base of workstations.

II. 90 degree paradigm: Initial observations and questions ∧

• It is unclear as to exactly WHY any of the elements in the instructions are deemed to be capable of ensuring health. This seems to be based on something called “neutral body positioning”. From OSHA’s eTools: “To understand the best way to set up a computer workstation, it is helpful to understand the concept of neutral body positioning. This is a comfortable working posture in which your joints are naturally aligned. Working with the body in a neutral position reduces stress and strain on the muscles, tendons, and skeletal system and reduces your risk of developing a musculoskeletal disorder (MSD)….” eTools then gives a set of guidelines resulting in the 90 degree paradigm, with minor variations being shown on the site;

• Relative to the above, scientific support for the terminology is unclear. One can find a patchwork of isolated studies but much of what is presented seems to be a combination of opinions, “common sense”, and a priori assumptions developed by people working in the discipline of ergonomics. The reasoning behind the concept of “neutral” in the proffered body position cited above is an example; it is just as easy to argue that the position is one of stress — confirmed by the model’s requirement of periodic breaks from the position — and that there is in fact nothing “neutral” about it. Nor is there any reason to accept that the joints in the position as presented are “naturally aligned”;

• The paradigm makes no distinction between “task”, or short term sitting, toward which it seems to be directed, and long term or “marathon” sitting, for which it would seem to be singularly unsuited. The failure to establish or even acknowledge the obvious and critical distinction between short and long term sitting calls into question the very model itself. Task, or short term sitting denotes someone such as a receptionist who may be up and down from their seat every 15 minutes over a range of 5-8 hours; long term, or marathon sitting is very different and involves much longer periods of 8-14 hours per session such as required by call centers, animators, engineers, drone operators and many others;

• The paradigm omits critical gravitational references from its presentation. Load, weight bearing surface, footprint and angles of support are primary issues in workstation engineering that a perceptive builder would clearly define at the outset and maintain through the design process. We see no evidence of proper consideration of these factors in the final 90 degree model;

• The paradigm always presents with young, healthy subjects of perfect body mass as its subject. Proponents of standing workstations engage in the same deception. This bears no relation to reality as it exists in the modern workforce;

• The paradigm omits discussion of workplace seating disease almost entirely. We do get mention of avoiding “musculoskeletal disorder” but degenerative disc disease as it relates to the spine, diseases of the extremities as they relate to leg positioning, aging and its effect on one’s ability to sit are not even mentioned. It can no longer be pretended that these are not important or relevant, and we will go into some detail on this below.

III. Key issues in workstation design ∧

• When designing a workstation we must put the biomechanical needs of the human being at the fore of our process. We must enable worker comfort, ensure worker health and enhance worker productivity. Taken together, these three factors should lead to a happy and content worker, one who looks forward to his or her work and sees the workstation as an attractive and inviting place to be. The inability to achieve any one of these goals means we do not have a design. These are surprisingly difficult metrics to achieve, and measured on the basis of medical impacts alone the current state of affairs can only be assessed as failure;

• Further, any seating model that purports to mate a human being with a workstation must make a distinction between short and long term sitting. Receptionists and office managers work differently than engineers and animators, and proper workstation design must keep this in perspective;

• On average someone may spend as much as 15 hours a day in a seated position; eight or more of those hours may be at a workstation. That’s some 2000 work hours per year, 10,000 in five. Certainly there are those who sit less. Still, for most people sitting is not a short term activity. It is a marathon, and the average human being in the west begins his or her inquiries in a school desk and occupies a workstation chair well into the third trimester of life. The development of degenerative disease during this journey must understood, monitored and minimized proactively wherever possible.

IV. Detailed observations: The building and accumulation of stress ∧

• The first observation is that the 90 degree model is backwards. As stated above, this is an effort to interface a human being with a workstation by shaping that human to occupy a conventional chair. If we were to build by fully accommodating the biomechanical needs of the human we would have a completely different plant. It is the design of the conventional workstation and its chair that is incorrect, not the human approach to that workstation; and yet the model assumes exactly the opposite and tries to correct the human;

• The model forces the a priori assumption that a “correctly” curved upright spine is a desirable  position, but in fact two issues, that of spinal compression and a 2006-07 study by Waseem Bashir (see below) shed serious doubt on this assumption. While spinal compression may not be an issue for a few hours a day among the young and healthy the cumulative effects over thousands of hours are far less certain. Degenerative disc disease is a condition associated with aging in which the cushioning material throughout the spine, particularly the lower back, diminishes significantly. What role spinal compression plays in the development of the condition is unknown, but it can, in many cases, develop into debilitating lower back trauma. Trying to maintain this upright position for extended periods of time is absolutely impossible for millions of back trauma sufferers;

position, but in fact two issues, that of spinal compression and a 2006-07 study by Waseem Bashir (see below) shed serious doubt on this assumption. While spinal compression may not be an issue for a few hours a day among the young and healthy the cumulative effects over thousands of hours are far less certain. Degenerative disc disease is a condition associated with aging in which the cushioning material throughout the spine, particularly the lower back, diminishes significantly. What role spinal compression plays in the development of the condition is unknown, but it can, in many cases, develop into debilitating lower back trauma. Trying to maintain this upright position for extended periods of time is absolutely impossible for millions of back trauma sufferers;

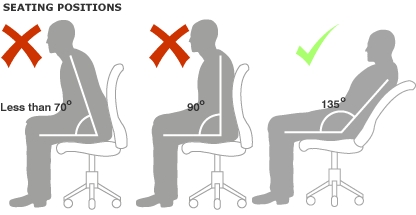

• The upright position is seen as an anti-slumping mandate, but the Bashir study cited below, which calls for a 135 degree posture rather than 90, points to “slumping” as being nothing more than the body’s attempt to correct an incorrect posture with a more biomechanically correct one. Slumping is generally graphically represented with the spine in a contorted position, but the issue is more complex;

• Also, the model frequently, but not always, presents with a 90 degree seat pan/hip angle. When it does so it is biomechanically incorrect. A 90 degree hip angle actually forces the curve at the small of the back OUTWARD, not inward, as is desirable, and constant stress is a result. This is why users beg for lumbar support: it is needed to offset the outward pressure built on the lower spine by an incorrect seat pan tilt. But applying inward lumbar pressure on the back when the hips are pushing it outward just increases stress and inflammation and is a major source of low back pain;

• To enable the curve at the small of the back the hips should tilt forward at about 8 degrees or so, not be held horizontally. The model does, with variations, occasionally present in this fashion and some chairs do in fact enable forward seat pan tilt. But the posture tires quickly, cannot be held for extended periods and is not an attractive alternative for most sitters. This simply emphasizes the fact that the model is uniquely suited toward short term sitting;

• As stated above the most important factor to keep in mind when designing a workstation coupled with a chair is gravity. This simple fact of engineering has eluded modern workstation designers completely. Gravity at a workstation manifests as three variable constants: Load, weight bearing surface, footprint and to this we add angles of support. The 90 degree model fails to balance these critical factors effectively and thus creates a situation of continual stress. A more specific explanation:

• The entire weight [load] of the body is focused for extended periods of time on the buttocks and upper thighs, a [footprint] that is too small for long term sitting. Muscles, skin, nerves, bones and spinal disks are all crushed in this position, and circulation is impeded; hence one of several needs for a break to relieve pressure and get the blood flowing again;

• Further, a user of this position will be entirely at the mercy of the designer of his or her seat pan, or [weight bearing surface]. Thin, hard seat pans here become torture over extended periods. Careful consideration must be given to the design of a seat pan, including the use of quality foams and gel materials, but good luck on finding such construction in a modern conventional chair. This is why so many are forced to augment their chairs with add on cushioning;

• Finally, proper calculation of the [angles of support] is critical. Task, or short term seating devices have very limited variation in the angles of support, while a design oriented toward long term sitting has a far greater range;

• The 90 degree angles at the joints are simply too severe to maintain for extended periods (see Bashir below). The model tells us that the joints are presented as “naturally aligned”, but there is no reason to accept this proposition. Holding +/- 90 degree angles for extended periods, even with interruptions, results in pain and inflammation in the joints and undesirable disk movement in the spine, hence the extreme relief associated with stretching. And the 90 degree angles at the hips and knees and relentless pressure on the upper thighs creates circulatory issues with the legs;

• There is absolutely no rational or biomechanical reason to keep one’s feet “flat on the floor” while seated. This came out of early observations by ergonomists that some users of office chairs were not using the mechanical height adjustments properly and were actually letting their feet dangle in midair; hence the evolving model insisted that feet contact the floor or, alternatively, a foot rest. But the medical community has for years been linking stress created by extended sitting and standing to a variety of diseases of the extremities including deep vein thrombosis. Elevating the legs to the point where they are in a reduced horizontal incline relative to the heart is what is clearly desirable, and here the model fails completely;

• There is absolutely no rational or biomechanical reason to keep one’s feet “flat on the floor” while seated. This came out of early observations by ergonomists that some users of office chairs were not using the mechanical height adjustments properly and were actually letting their feet dangle in midair; hence the evolving model insisted that feet contact the floor or, alternatively, a foot rest. But the medical community has for years been linking stress created by extended sitting and standing to a variety of diseases of the extremities including deep vein thrombosis. Elevating the legs to the point where they are in a reduced horizontal incline relative to the heart is what is clearly desirable, and here the model fails completely;

• Relative to all of the above the posture is untenable for anyone with diseases of the extremities, phlebitis, diabetes, circulatory or weight issues, or a host of other problems, and that is a big chunk of the population. The model impedes rather than enhancing good blood circulation and thus overall health is degraded.

V. The insertion of “breaks”: An endless cycle of interrupting stress ∧

• The designers of the 90 degree paradigm have built their model on the basis of what they present as a “body neutral” position. The term carries with it a priori assumptions that we are supposed to accept at face value, chief among those being that this is a relaxed position in which the body can remain for an extended period. This is simply not true. Stress is constantly building in the position and for that reason the designers of the model advocate the taking of periodic “breaks” to offset the inevitable consequences. In this respect the model directly contradicts itself;

• Workstation stress is a message from the body than an imbalance among the forces of gravity on the body has been created and that a change is mandated. Stress is a serious biomechanical message; if left unanswered it turns into pain, and then chronic pain. Degenerative disease is just around the corner;

• You need to keep breaking the position because discomfort builds in a static position to the point where it is simply intolerable and a worker has no choice but to completely interrupt it. There is no other position to assume, and one has to continuously return to the same posture which had become untenable just before the break. Rather than having defined the perfect “neutral body position” one can say that the 90 degree paradigm is an unnatural posture suitable for short term task purposes ONLY, and which may in fact carry with it long term health consequences;

• This insertion of breaks into the process of seating creates an endless cycle of creating and then attempting to relieve stress. If you see the model as anything different, you are missing the point. The builders of the 90 degree paradigm do not address the issue of this endless cycle, which is repeated thousands of times over the years, and its potential long term effects on the human body;

• Movement is the current hot topic in workstation design, and that fact alone points to awareness on the part of the office seating industry that all is not perfect in what it has built. Movement is here being equated with health; the issue of comfort is more clouded. But just how to incorporate movement into the workstation while maintaining productivity is surprisingly difficult. The solution at the present is to preserve the static model of sitting and enable movement, or breaks, as a separate part of the design.

VI. The nature of breaks: Method, duration and effectiveness ∧

• What a break is, how to put it into effect and how long one should last are all open questions. There are, in fact, numerous suggestions among presenters of the model ranging from 5 to 10 minutes per hour, some of which are mandated. Actual definitions of what constitutes a biomechanically meaningful offset break are lacking. In this case, one would be seeking to effectively offset the accumulation of stress that has built up in the position. In reality, no one knows;

• Most simply, a seated user does NOT have to get up and leave the workstation to effect movement. All one has to do is stand up and stretch toward the sky, do some twists, sit back down and repeat the cycle a dozen times or so, three times in the morning and three times in the afternoon. There are many variations of this and advocates of just such workplace exercises have been working the internet for years. Actually making this happen regularly in our 2000 hour per year theater requires significant dedication and self discipline, and there is no guarantee that this will be a useful offset to the ills of sitting itself;

• This is the direction in which the current “sit-stand” models are evolving and among “standing”, sit-stand and “treadmills” (SST), sit-stand is the only one that makes any sense. Whether or not this type of movement can actually offset the diseases of sitting is unclear; current studies seem to equate chaired workstations with nuclear waste dumps and, well, clarity is here not rampant;

• But the fact remains that most workers do NOT seem to incorporate these movements into their daily routines and we have a crisis of biblical proportions at the modern workstation. The issues of motivation, self discipline and perception of reward in the form of actual health benefit are here paramount. We are once again left with the question of, do we have a plan, and, if so, how do we put it in to effect and measure the benefits?

VII. Breaks and productivity ∧

• Relative to the above, there is little to no accounting for the actual time devoted to breaks from the model. At 5 minutes every 30, a commonly cited recommendation, the amount of time allocated to breaks amounts to 17% of total work time, some 42 days per year or two full months out of 12. This figure must be added to all other recommended or mandated breaks, and is never cited anywhere. Just as the builders of the 90 degree paradigm do not address the problem of the endless cycle of breaks, they say nothing about the time that must be dedicated to them. Nor is there any possibility of control over how long a break should be. 5 minutes easily turns into 10…

• These discontinuous breaks or interruptions from the position have a severely negative effect on productivity. A worker is, in general, advised to get up and stretch or leave his or her workstation completely every 30 minutes, 16 times per day, 4000 times per year. The actual numbers will inevitably be less. Sounds simple. But mandating a standard and actually getting it to work over extended periods are two different things. “They don’t just take breaks”, the supervisor of one call center told me about her team of engineers. “They get up and walk away.” Apparently this constant cycle of stopping and starting over again is at its core unnatural and creates its own discontinuity that in the end is unsustainable. The breaks get longer, the returns to work less productive, the monotony of the cycle unbearable. And at the core of this discontent lies the perception, perhaps subconscious, that the workstation itself is a singularly unattractive place to be.

VIII. Summary and Conclusions ∧

• The 90 degree paradigm is the sole instruction set currently in use to define the interface between a human being and a workstation using a conventional chair. The model presents with key a priori assumptions which weaken under scrutiny. Chief among those is the “neutral body position” which by its very nature is constantly building up stresses that must be offset by a constant cycle of interruptions or breaks. The long term effect of this cycle is unknown;

• The model, which is based on a single static position, is only suited toward short term or “task” seating, a position which a user will hold for 15-30 minutes at a time before seeking relief;

• Elaborating, the model, which makes no distinction between short and long term seating, is singularly unsuited for the latter;

• Attempting to effect the position over extended periods of time may lead to serious degenerative health problems, this being the opposite of what its proponents maintain. Herein the paradigm is not being seen as the solution to, but rather a significant cause of, workstation seating disease, which is prevalent and widespread;

• Serious questions center on degenerative disk disease as related to the upright posture of the spine; low back pain, as related to hip positions; diseases of the extremities as related to the mandated position of the legs and feet; aging, as it relates to the ability to maintain the posture for any extended period, and problems related to obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular conditions and any other health issue where extended sitting is identified as a known risk or exacerbatory factor;

• Lack of engineering detail in the areas of load, weight bearing surface, footprint and angles of support make the design as presented untenable for long term sitting;

• The quality and actual biomechanical effectiveness of breaks, productivity questions relating to the constant need for breaks and time factors related to those breaks are serious and generally unaddressed issues. The difficulty of implementation and management here makes an acceptable resolution unlikely.

The 90 degree posture wasn’t developed because it is the best possible way to sit at a workstation. It was developed because there was a need to fit a human being into a workstation and, lacking any realistic alternatives, this is the best anyone could come up with at the time. Stated differently, no one really thought this one through, and like all bad ideas that overstay their welcome the negative consequences of this one are becoming all too apparent.

This does not mean that the conventional workstation or seating paradigm should or will disappear. But alternative methods of seating are clearly needed, and the Renegade Space model is just such an alternative.

Bashir: The 135 degree study ∧

In 2006-07 Dr. Waseem Bashir from the Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging department of Canada’s University of Alberta Hospital and some colleagues in Scotland produced a study in which it was ascertained that the preferred body angles of sitting were in fact 135 degrees, not the 90 that conventional wisdom was proffering as a model of workplace seating health. Using a positional MRI scanner the team determined that there was less undesirable disk movement at the “relaxed” position of 135 degrees then at that of 90. “This may be all that is necessary to prevent back pain, rather than trying to cure pain that has occurred over the long term due to bad postures,” Bashir stated. “Employers could also reduce problems by providing their staff with more appropriate seating, thereby saving on the cost of lost work hours.”

Although it was never stated as such, Bashir and his colleagues were simply studying ways to counteract the negative effects of gravity on the human frame. The study was widely cited at the time and then completely disappeared from the radar. No subsequent ergonomic studies were initiated based on Bashir’s work, and no manufacturer tried to bring a device to market that would enable the postures the study called for. “Really the best position is what you get in a La-Z-Boy, although that wouldn’t work well for someone using a computer,” was Bashir’s comment at the time, and the feeling was echoed by a few industry comments. But there were other problems with the study; let’s take a look.

While Bashir and his colleagues were criticizing the 90 degree posture they didn’t have an alternative seating device with which to really flesh out their theories. They had to use a conventional chair, which they never questioned, and this limited their options. Most critically, they did not address the issue of what must happen with the seat pan when the angle at the hips is increased from 90 to 135 degrees. They simply left the seat pan at the horizontal and pushed the upright position backwards. This results in a pronounced tendency to slide forward and off of the seat and creates its own issues of discomfort and usability.

Astonishingly, it seems to have never occurred to anyone at the time that simply tilting the seat pan to the rear would correct for this deficiency and make the position more workable. The overwhelmingly critical angle of the seat pan in this equation was never addressed and a true model of workplace reclining never developed. Of course that would mean one would have to elevate the legs and, well, that just wasn’t going to happen.

Post Bashir: Why has change been slow to arrive? ∧

Part of the problem is cultural, and this could well be why chairs are not as comfortable as their builders maintain. They are SUPPOSED to be uncomfortable, because that’s how you stay awake and get work done. The reclining position advocated by Bashir has always been seen by corporate America as somewhat akin to “Miller Time” and goofing off. Reclining is really just “slumping”, and slumping is not appropriate for a work environment. When one does lean back, it is measured and temporary. “We design our (Herman Miller) chairs so that people can change positions regularly,” stated ergonomist Judy Lesse in response to Bashir. “You may find it difficult to lean back while using a computer, but you can lean back while talking on the phone.”

In any case, Bashir’s model was entirely incomplete and without a device to make it possible it was simply forgotten. That brings us to another part of the problem, and perhaps the biggest one, that of the mechanical. “Getting a 135-degree posture is optimal to minimize stress to the discs, but when you’re working, you cannot always achieve that,” orthopedist Gunnar Andersson said at the time. “You have to be practical.” Which means, in simple terms, we don’t have a clue how to make this reclining thing happen.

Beyond that it is tempting to see the modern workstation as one of Thomas Kuhn’s paradigms. The US office furniture industry is valued at some $23 billion annually, and at its core is a chair and desk designed on the 90 degree paradigm, a model of sitting that simply can not and does not work for the long term seated user. While no one expects the conventional model to disappear completely it is obvious that alternatives are badly needed. The industry is aware that changes need to be made and the current movement toward standing and sit / stand designs is indicative of that awareness. But these solutions have their own weaknesses and will have little real impact on the overall problem of workplace seating. Other ongoing industry efforts at change seem to be centered on little more than a reshuffling of outdated ways of thinking.

“The Future of Ergonomic Office Seating” ∧

In 2010 Knoll, a major manufacturer of office seating in the United States, published a remarkable document entitled “The Future of Ergonomic Office Seating” by Tim Springer of HERO Inc., among other credits. “Sitting is an activity – It’s something people do”, wrote Springer. “Sitting is active, involving motion, balance, position, posture, and control. Sitting is an innate behavior involving both body and mind. Sitting is natural. People sit in a wide variety of ways and places. People don’t need to learn how to sit. Sitting is simple.” The document goes on to describe the chair of the future: “…at a minimum, the next generation office chair will fit your body, not just the dimensional criteria of some published standard. It will be stable, yet promote dynamic, active, natural motion allowing sitting in any position. The chair will support you in all the various activities comprising your work day: from sitting at a computer to talking on the phone to interacting with others; from turning or reaching to bending or stretching. The chair supports you in whatever position you feel most comfortable. The chair will support both the physical and cognitive nature of your work enabling you to be more efficient and effective. It will be simple, natural and easy, intuitive and enjoyable to use.”

Springer was describing the chair designed and expounded upon by Renegade Space in these pages.